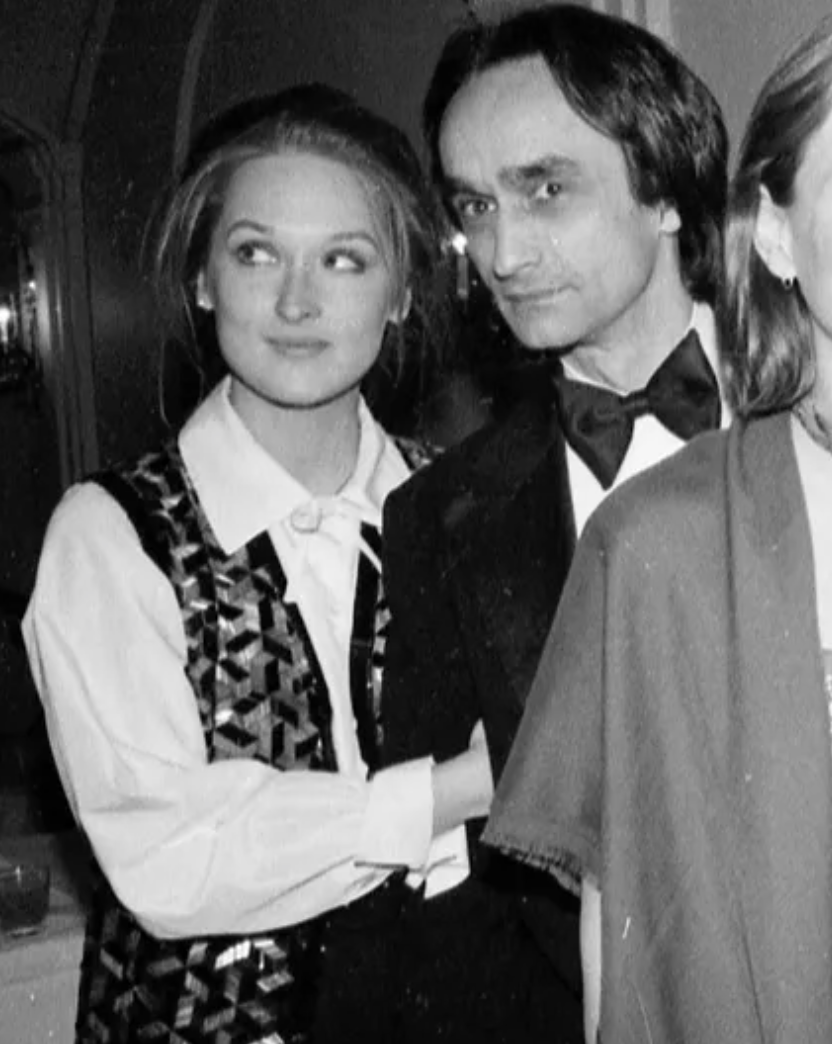

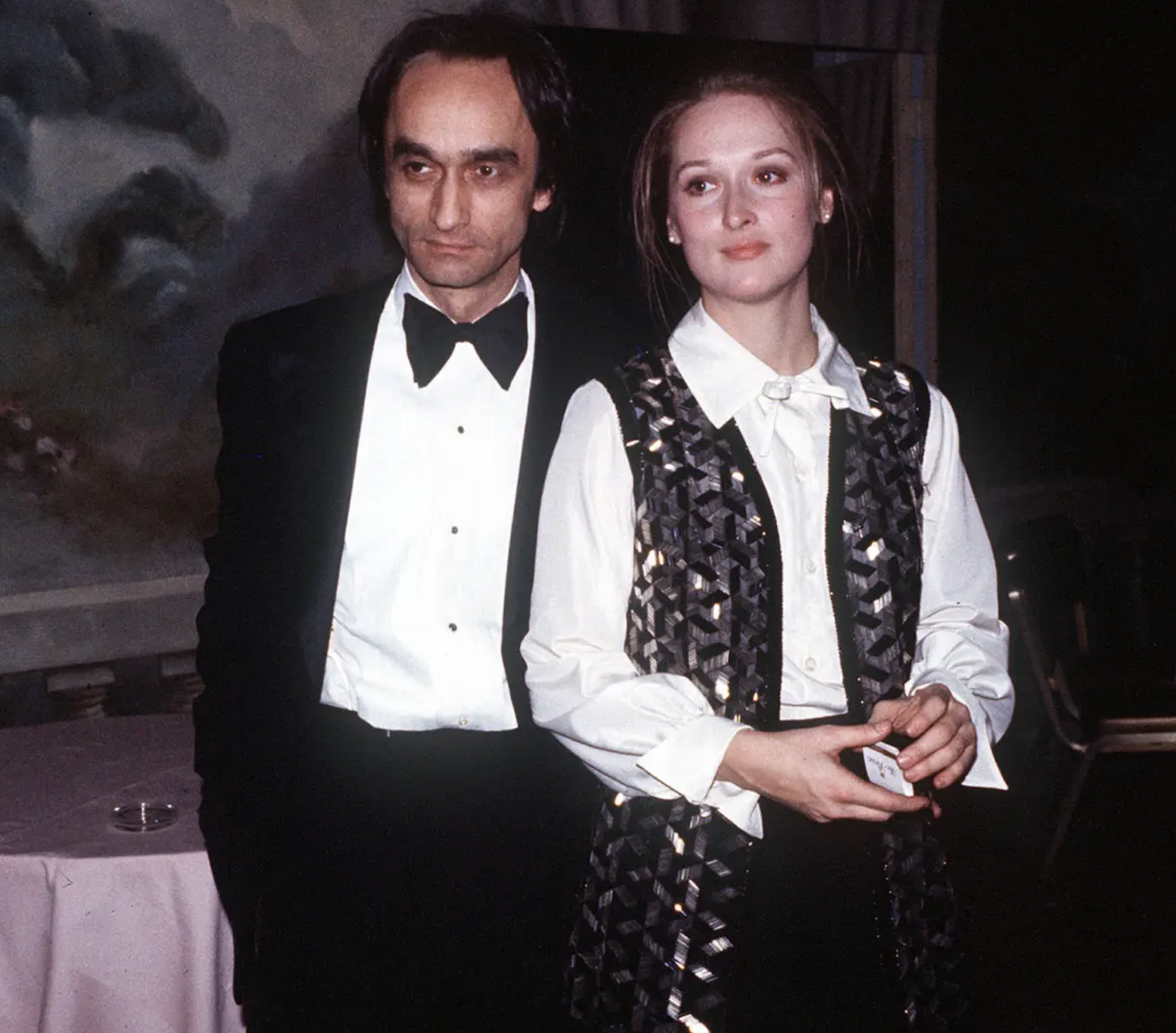

The tragic romance that shaped Meryl Streep’s life

In 1978, a young Meryl Streep stood on the brink of becoming the preeminent actress of her time. However, she was also on the verge of losing the love of her life.

Michael Schulman, in his new biography “Her Again,” delves into this period, stating, “She doesn’t discuss it often, but that year was incredibly tumultuous and significant in her life. It played a pivotal role in shaping both her personal and professional identity.”

At 29, Streep was a fledgling figure in the New York theater scene, residing in a loft on Franklin Street with her boyfriend, actor John Cazale. Cazale, who was 14 years her senior, was revered among his peers and had a profound impact on Streep’s approach to acting.

Al Pacino once remarked, “I learned more about acting from John than anybody else. All I wanted was to collaborate with John for the rest of my career. He was my acting partner.”

Streep and Cazale crossed paths in 1976 during their casting in “Measure for Measure” at Central Park. At the time, Cazale hadn’t quite attained star status, but he possessed a rare talent highly sought after by the industry’s top directors.

Cazale’s roles in “The Godfather” series, “The Conversation,” and “Dog Day Afternoon” showcased his remarkable acting abilities. Each of the five films he starred in earned Best Picture nominations, with three winning the prestigious award.

Director Sidney Lumet noted, “One of the things I admired about John Cazale’s casting was his profound sense of sadness. I can’t explain its origin; I believe in respecting the privacy of the actors I collaborate with. But it’s undeniable — it permeates every frame he’s in.”

According to Schulman, “Time moved differently for John Cazale. Everything seemed to unfold at a slower pace. He wasn’t unintelligent, far from it. Yet, he was painstakingly methodical, sometimes to the point of frustration.”

Directors affectionately dubbed him “20 Questions” for his insistence on thorough character background. Pacino described even a simple dinner with Cazale as an elaborate affair: “By the time he finished half of his meal, we would be done, cleaned up, and ready for bed. Then he would bring out his cigar. He’d examine it, light it, savor it, and only then would he smoke it.”

Cazale’s distinctive appearance, characterized by his slim frame, high forehead, prominent nose, and melancholic black eyes, perfectly suited the outcasts of 1970s cinema.

Streep and Cazale were immediately smitten with each other, forming an instant connection.

“After he landed that role,” actor Marvin Starkman recalled, “all he could talk about was her.”

Cazale’s appearance and demeanor were entirely different from those Streep had encountered before.

“He was unlike anyone I had ever met,” she later reflected. “It was his uniqueness, his humanity, his curiosity about people, his compassion.”

While Cazale was the more recognized figure of the two, they were still struggling artists. When they dined in Little Italy, restaurant owners, thrilled to have Fredo among them, insisted they dine for free.

“They were fascinating to observe because they were both rather eccentric-looking,” noted playwright Israel Horovitz. “They were charming in their own way, but they were a truly quirky couple. They turned heads, not because of her beauty, but because they were so unusual.”

As Schulman writes, “their love story moved as slowly as John did,” and before long, they were happily cohabiting in Cazale’s Tribeca loft.

The envy of the New York theater scene, Streep, the most naturally gifted actress of her generation, and Cazale, the most naturally gifted actor, enjoyed the patronage of legendary director Joe Papp. However, their happiness was shattered one day in May 1977.

During previews for “Agamemnon,” Cazale fell ill, prompting Papp to arrange an urgent appointment with his own doctor. Within days, Streep and Cazale sat with the Papps in the doctor’s office, receiving the devastating news: Cazale had terminal lung cancer, metastasized throughout his body.

The news stunned them all into silence.

“John fell silent,” Schulman recounts. “For a moment, so did Meryl. But she was never one to surrender, certainly not to despair… She looked up and asked, ‘So, where should we go for dinner?'”

Cazale withdrew from his play immediately, while Streep continued her role in the musical “Happy End” without showing signs of anxiety or grief. Though Cazale occasionally visited the theater, still indulging in his cigars, Streep didn’t admonish him. Instead, she made her dressing room off-limits to smokers, displaying remarkable grace beyond her years.

“She had this kind of tough love approach,” recalled actor Christopher Lloyd. “She didn’t allow him to wallow.”

Streep and Cazale attempted to keep the severity of his illness private, even from his brother, Stephen. It wasn’t until Cazale coughed up blood on a Chinatown sidewalk that Stephen realized the gravity of the situation.

Al Pacino accompanied Cazale to radiation treatments, hoping against hope for a positive outcome. Cazale himself remained determined to recover, even insisting on returning to work. In solidarity, Streep accepted a role she despised just to remain by his side.

“I was just ‘the girl’ in the movie,” Streep explained, “essentially a man’s perspective of a woman. She’s extremely passive, very quiet, constantly vulnerable.”

In essence, she embodied everything Streep lacked. However, the film in question was “The Deer Hunter,” offering Cazale the opportunity to star alongside Robert De Niro in one of the few cinematic explorations of the Vietnam War at that time.

Despite resistance from the production company, EMI, who insisted on Cazale’s dismissal due to exorbitant insurance costs associated with his illness, the filmmakers fought to keep him on board.

Director Michael Cimino recalled the ordeal, stating, “I was told that unless I got rid of John, [they] would shut down the picture. It was awful. I spent hours on the phone, yelling and screaming and fighting.”

According to Streep’s account, De Niro covered Cazale’s insurance expenses, although this claim remains unverified by Cazale himself. De Niro later remarked, “He was sicker than we thought, but I wanted him to be in it.”

Despite Streep’s desire to cease working and be by Cazale’s side, financial burdens compelled her to accept a leading role in the nine-hour TV miniseries “Holocaust,” solely for the paycheck.

Filmed in Austria, “Holocaust” posed logistical challenges as Cazale’s declining health prevented him from accompanying Streep. Although Streep maintained a facade of “cheery professionalism,” she privately struggled with the grim nature of the material and the emotional toll of their separation.

After returning to New York, Streep found Cazale in a deteriorated state, prompting the couple to retreat from public view for five months. Streep dedicated herself entirely to Cazale’s care, attending every medical appointment and radiation session without betraying her resolve.

Reflecting on their time together, Streep acknowledged that their seclusion provided a peculiar form of sanctuary. “I was so immersed,” she revealed, “that I didn’t notice the deterioration.”

Despite her outward composure, Streep confided in only a select few, including her former drama teacher at Yale, Bobby Lewis, about her true emotional turmoil.

“My beloved is gravely ill and at times, like now, in the hospital,” Streep penned. “He receives exceptional care, and I strive not to linger fretfully, but I am consumed by worry constantly, pretending to maintain cheerfulness, which is more mentally, physically, and emotionally draining than any work I’ve ever done.”

In early March 1978, Cazale was admitted to Memorial Sloan Kettering. Streep remained steadfast by his side. At 3 a.m. on March 12, 1978, Cazale’s physician informed Streep, “He’s passed away.”

“Meryl wasn’t prepared to hear it, let alone accept it,” Schulman recounts. “What unfolded next, according to some, was the culmination of all the persistent hope Meryl had harbored over the past 10 months. She pounded on his chest, crying, and for a brief, startling moment, John opened his eyes. ‘It’s all right, Meryl,’ he weakly uttered. ‘It’s all right.’ Then he closed his eyes and passed away. Streep’s initial call was to Cazale’s brother, Stephen, as she wept inconsolably.”

That year, Streep achieved a series of triumphs: She earned an Emmy for “Holocaust,” an Oscar nomination for “The Deer Hunter,” secured a career-defining role in 1979’s “Kramer vs. Kramer” — which garnered her the Academy Award — and landed the part of Kate in Shakespeare in the Park’s “The Taming of the Shrew.” She ascended to stardom.

However, Cazale’s demise and her personal anguish had profoundly altered her, both as an individual and an actress.

Her portrayal of Kate took on a new perspective: She wasn’t merely an independent woman susceptible to a man’s dominance, but one who discovers profound fulfillment in surrendering to love.

“I’m expressing, ‘I’ll do anything for this man,'” Streep elucidated to a reporter at the time. “Consider this, would there be any qualms if a mother were speaking of her son? Service is the essence of love. Everyone is preoccupied with ‘losing oneself’ — all this self-absorption. Duty. We shun that notion too… But duty might be the armor you don to fight for your love.”

Despite her subsequent accolades — 19 Academy Award nominations, the most of any actress in history, and three wins — her peers and fellow actors hold Streep in highest esteem for her unwavering commitment to Cazale, recognizing the fortitude of character displayed by such a young woman.

“She tended to him as if there were no one else in the world,” remarked Joe Papp. “She never wavered in his presence or absence. Never gave any indication that he wouldn’t make it.”

Al Pacino echoed similar sentiments. “When I saw that girl with him like that, I thought, ‘There’s nothing like that.’ I mean, that’s it for me. As incredible as she is in all her work, that’s what comes to mind when I think of her.”